Behind the Investigation: Real Stories. Real Lessons. Community Impact.

Go beyond the classroom and into the field with stories, insights, and strategies drawn from real Tribal investigations and training experiences. This is where cultural knowledge meets practical action — all to strengthen our communities and protect what matters most.

Yearly Reflection: Our Communities, Our Responsibility

As we close out another year, we’re reminded that reflection is more than looking back — it’s honoring the relationships, lessons, and commitments that shape our purpose. For PSC, 2025 was a year of growth, adaptation, and meaningful partnership. Despite shifting landscapes in Tribal funding, training access, and technology, our mission remained unwavering: Our communities, our responsibility. This year affirmed that commitment more deeply than ever. Celebrating Our 2025 Achievements Advancing Training Excellence Across Indian Country We were honored to host our Second Annual Adjudicator’s Training Conference, bringing together professionals committed to strengthening investigative practices and Tribal workplace integrity. Each year, this conference not only

Yearly Reflection: Our Communities, Our Responsibility

As we close out another year, we’re reminded that reflection is more than looking back — it’s honoring the relationships, lessons, and commitments that shape our purpose. For PSC, 2025 was a year of growth, adaptation, and meaningful partnership. Despite shifting landscapes in Tribal funding, training access, and technology, our mission remained unwavering: Our communities, our responsibility. This year affirmed that commitment more deeply than ever. Celebrating Our 2025 Achievements Advancing Training Excellence Across Indian Country We were honored to host our Second Annual Adjudicator’s Training Conference, bringing together professionals committed to strengthening investigative practices and Tribal workplace integrity. Each year, this conference not only

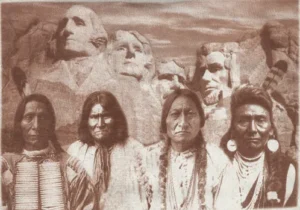

Building Sovereignty Through Knowledge

This month, I’m reflecting on what sovereignty means beyond legal status. For me — as an enrolled member of the Navajo Nation — sovereignty is about what we do with what we know. It’s not just a word on a tribal resolution or a federal document. It’s the action of building

You ever get one of those emails that just doesn’t feel right?We did — and it came from someone our team has emailed a hundred times before. A Tribal court clerk.No greeting. No “Hi,” no “Good morning,” nothing — just an attachment. And in our world, attachments mean business —